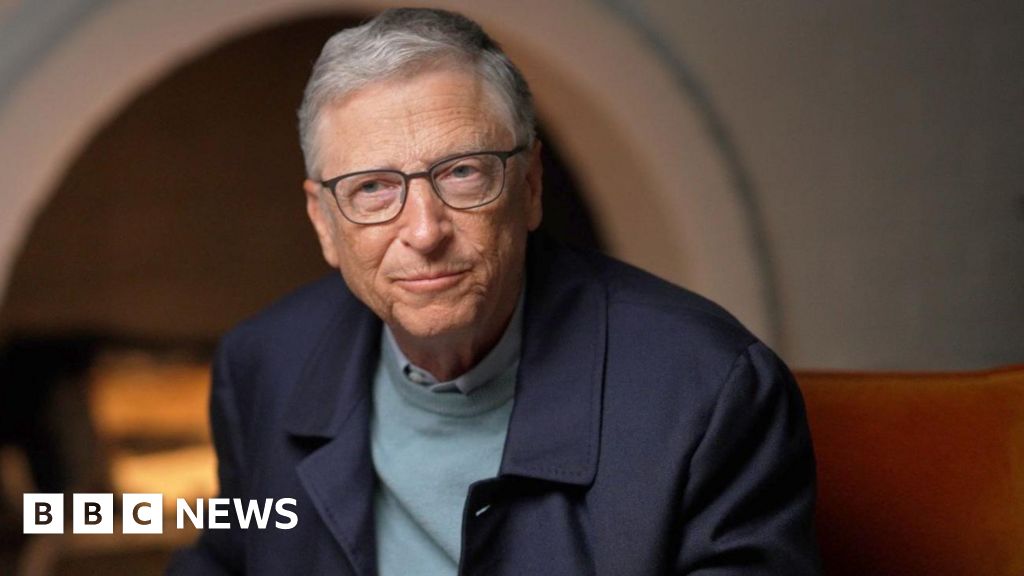

Maxine Collins/BBC

Maxine Collins/BBCIt’s towards the end of our interview that Bill Gates reveals new numbers on how much his charitable Foundation has now spent in its efforts to combat preventable diseases and reduce poverty.

“I’ve given over 100 billion,” he says, “but I still have more to give.”

That’s dollars, just to clarify, worth about £80bn.

It’s roughly equivalent to the size of the Bulgarian economy or the cost of building the whole HS2 line.

But to put it in context, it’s also around the same as just one year of Tesla sales. (Tesla owner Elon Musk is now the richest man on the planet, a position Gates held for many years.)

The co-founder of Microsoft and his fellow philanthropist Warren Buffett are combining their billions through the Gates Foundation he originally set up with his now ex-wife Melinda.

Gates says philanthropy was instilled in him early on. His mother regularly told him “with wealth came the responsibility to give it away”.

The plan had been to unveil the $100bn figure in May, for the Foundation’s 25th anniversary. But Gates revealed it exclusively to the BBC.

He tells me, for his part, he enjoys giving his money away (and around $60 billion of his fortune has gone into the Foundation so far).

When it comes to his day-to-day lifestyle, he doesn’t actually notice the difference: “I made no personal sacrifice. I didn’t order less hamburgers or less movies.” He can also, of course, still afford his private jet and his various huge houses.

He plans to give away “the vast majority” of his fortune, but tells me he has talked “a lot” with his three children about what might be the right amount to leave them.

Will they be poor after he’s gone? I ask him. “They will not,” he replies with a quick smile, adding “in absolute, they’ll do well, in percentage terms it’s not a gigantic number”.

Gates is a maths guy and it shows. At Lakeside School in Seattle, in eighth grade, he competed in a four-state regional maths exam and did so well that, at 13, he was one of the best high school maths students of any age in the region.

Maths terminology comes second nature to him. But to translate, if you’re worth $160bn, which Bloomberg’s Billionaires Index claims he is, even leaving your children a tiny percentage of your fortune still makes them very rich.

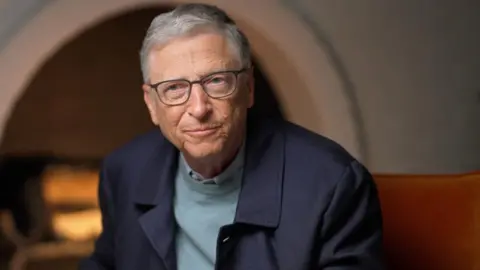

Maxine Collins/BBC

Maxine Collins/BBCI’m with one of only 15 people on the planet who are centibillionaires (worth more than $100bn), according to Bloomberg. We’re in his childhood home in Seattle, a mid-century modern four-bedroom house set into a hill, and we’re meeting because he’s written a memoir, Source Code: My Beginnings, focusing on his early life.

I want to find out what shaped a challenging, obsessive child who didn’t fit the norm into one of the tech pioneers of our age.

He’s brought along his sisters, Kristi and Libby, and all three excitedly tour the home where they grew up. They haven’t been back in some years and the current owners have refurbished (fortunately, the Gates siblings seem to approve of the changes).

But it’s bringing back memories including, as they walk into the kitchen, of the now-long-gone intercom system between rooms beloved by their mother. She used it to “sing to us in the morning”, Gates tells me, to get them out of their bedrooms for breakfast.

Mary Gates also set their watches and clocks eight minutes fast so the family would work to her time. Her son often rebelled at her efforts to improve him, but now tells me “the crucible of my ambition was warmed through that relationship”.

He puts his competitive spirit down to his grandmother “Gami”, who was often with the family in this house and who taught him to outsmart the competition early on with games of cards.

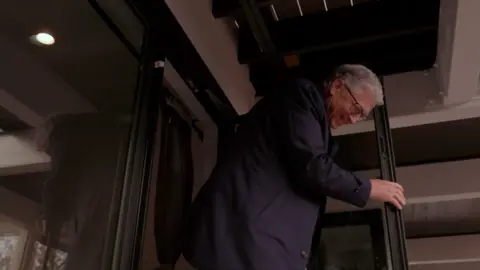

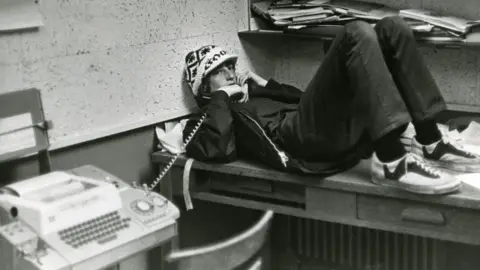

Maxine Collins/BBC

Maxine Collins/BBCI follow him down the wooden stairs as he heads off to find his old childhood bedroom in the basement. It’s a neat guest room now, but young Bill spent hours, even days, in here “thinking”, as his sisters put it.

At one point, his mum was so fed up with the mess that she confiscated any item of clothing she found on the floor and charged her stubborn son 25 cents to buy it back. “I started wearing fewer clothes,” he says.

By this time, he was hooked on coding and, with some tech-savvy school friends, had been given access to a local firm’s one computer in return for reporting any problems. Obsessed with learning to program in those nascent days of the tech revolution, he would sneak out at night through his bedroom window without his parents knowing to get more computer time.

“Do you think you could do it now?” I ask.

He starts unwinding the catch and opens the window. “It’s not that hard,” he says with a smile as he climbs up and out. “It’s not hard at all.”

There is a famous early clip of Gates in which a TV presenter asks him if it’s true he can jump over a chair from a standing position. He does it right there in the studio. I’m in the Gates childhood bedroom for something that feels like “a moment”. The guy’s nearly 70. But he’s still game.

He seems at ease – and it isn’t just because we’re in a familiar environment. In the memoir, he’s revealed publicly for the first time that he thinks if he were growing up today, he’d probably be diagnosed on the autism spectrum.

The only time I met him before was in 2012. He barely looked me in the eye as we did a quick interview about his goal to protect children from life-threatening diseases. There was certainly no pre-interview small talk. I wondered after our interaction whether he was on the spectrum.

The book lays it out: his ability to hyperfocus on subjects he was interested in; his obsessive nature; his lack of social awareness.

He says at elementary school he turned in a 177-page report on Delaware, having written off for brochures about the state, even sending stamped addressed envelopes to local companies asking for their annual reports. He was 11.

His sisters tell me they knew he was different. Kristi, who’s older, says she felt protective of him. “He was not a normal kid… he would sit in his room and chew pencils down to the lead,” she said.

They’re obviously close. Libby, a therapist, tells me she wasn’t surprised to hear he believes he is on the spectrum. “The surprise was more his willingness to say ‘this might be the case’,” she says.

Gates Family

Gates FamilyGates says he hasn’t had a formal diagnosis and doesn’t plan to. “The positive characteristics for my career have been more beneficial than the deficits have been a problem for me,” he says.

He thinks neurodiversity is “certainly” over-represented in Silicon Valley because “learning something in great depth at a young age – that helps you in certain complex subjects”.

Elon Musk has also said he is on the spectrum, referencing Asperger’s syndrome. The Tesla, X and SpaceX billionaire is famously courting Donald Trump, as are the other modern-day tech bros, Meta’s Mark Zuckerberg and Amazon’s Jeff Bezos among other Silicon Valley attendees at Trump’s inauguration.

Gates tells me although “you can be cynical” about their motives, he too reached out to the president. They had a three-hour dinner on 27 December “because he’s making decisions about global health and how we help poor countries, which is a big focus of mine now”.

I ask Gates, himself a target of some pretty wild conspiracy theories, what he thinks of the decision taken by Zuckerberg after Trump’s election to dump fact-checking in the US on his sites. Gates tells me he’s not “that impressed” by how governments or private companies are navigating the boundaries between free speech and truth.

“I don’t personally know how you draw that line, but I’m worried that we’re not handling that as well as we should,” he says.

He also thinks children should be protected from social media, telling me there’s a “good chance” that banning under-16s, as Australia is doing, is “a smart thing”.

Gates tells me “social networking, even more than video gaming, can absorb your time and make you worry about other people approving you” so we have to be “very careful how it gets used”.

The Bill Gates origin story isn’t rags to riches. His dad was a lawyer, money wasn’t tight, although the decision to send their son to private school to try to motivate him was “a stretch, even on my father’s salary”.

If they hadn’t, we might never have heard of Bill Gates.

He first got access to an early mainframe computer via a teletype machine at the school, after the mothers held a jumble sale to raise the money. The teachers couldn’t figure it out, but four students were on it day and night. “We got to use computers when almost nobody else did,” he says.

Lakeside School

Lakeside SchoolMuch later, he would set up Microsoft with one of those school friends, Paul Allen. Another, Kent Evans, Gates’ best friend, would die tragically age 17 in a climbing accident. As we walk around Lakeside School, we pass the chapel where they held his funeral and where Gates remembers crying on the steps.

Together, they’d had big plans. When they weren’t on computers, they were reading biographies to work out what factors made people successful.

Now Gates has written his own. His philosophy? “Much of who you are was there from the start.”

The Making of Bill Gates is on BBC Two at 19:00 on Monday 3 February and on iPlayer

Source Code: My Beginnings is published on Tuesday 4 February