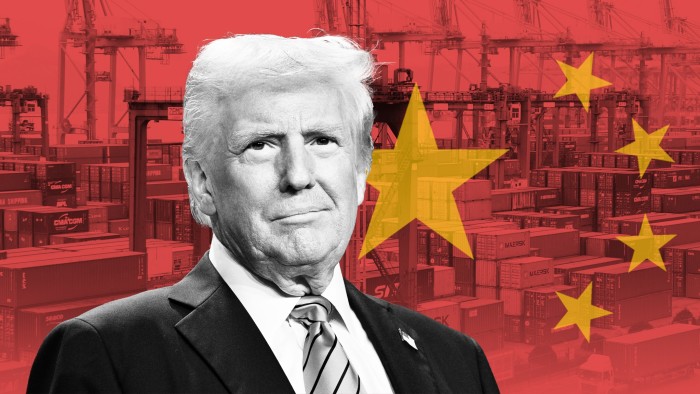

Chinese manufacturers say they will speed up efforts to move production to other countries to circumvent US tariffs, after President Donald Trump announced a new trade offensive against the world’s second-largest economy.

Beijing is considering how to retaliate against Trump’s decision on Saturday to impose an additional 10 per cent tariff on Chinese exporters, with options ranging from counter-tariffs to export controls and currency depreciation.

The relatively muted initial response from the Chinese government, combined with Trump’s truce with Canada and Mexico on Monday and his plans for a call with China’s President Xi Jinping in the coming days, have fuelled hopes in Beijing that there may be room for negotiation.

But with the tariff set to take effect on Tuesday, companies in China’s southern manufacturing heartlands said their strategies included moving some production to locations including the Middle East, passing the cost to US customers and seeking alternative markets.

“A lot of Chinese exporters, especially in the consumer products market, had already lost part of their US market over the past few years after tariffs kicked in,” said Michael Lu, president of China-based gift box producer Brothersbox, referring to levies Trump imposed as part of a trade war during his first term in office.

Lu said Brothersbox planned to move part of its production to the United Arab Emirates this year to target the US market. “We hope to win them back,” he said of his US customers.

Trump’s threat of an additional 10 per cent tariff on Chinese goods — which he attributed to Beijing’s alleged inaction on fentanyl exports to the US — was raised during his election campaign.

But Chinese companies have already been diversifying their trade in recent years. The country’s direct share of US imports fell eight percentage points between 2017 and 2023, according to a report by Rhodium Group last year.

Some Chinese production has moved to third countries, from where it is exported to the US. The share of US imports from Vietnam and Mexico, for example, increased substantially during the same period.

Lynn Song, greater China chief economist at ING, said the tariff would have a limited effect because “a lot of the price-sensitive exports to the US have already been redirected as a result of the first trade war”.

With Trump targeting Mexico, Chinese companies would probably shift more trade towards south-east Asia and Latin America, he said.

More sophisticated Chinese exports, such as machine parts, would also be difficult to substitute, meaning US buyers would have to absorb the price increases.

Tony Cao of Foshan Nanhai Yingya Hardware Products, a company in China’s southern Guangdong province that makes about 5 per cent of its sales in the US, said Trump’s tariffs would hit American importers harder than Chinese producers.

“They need to buy Chinese products,” Cao said. “Their procurement costs will increase and therefore their sales prices will rise correspondingly.”

Some analysts said the speed of the tariff’s promised implementation posed a challenge for Beijing, and questioned how much more Chinese manufacturing capacity could be easily moved abroad.

“Anybody who could [move supply chains] already has,” said Cameron Johnson, a partner at consultancy Tidalwave Solutions. Countries such as Vietnam, where Chinese companies have set up production lines, could also be hit by tariffs, he said.

“Anyone who has a significant trade surplus with the US is going to get some form of tariff,” Johnson said.

Amy Lin, a sales manager at Chinese footwear manufacturer Teshuailong, said overseas investment required more capital and manpower than her company could muster. Instead, Teshuailong would seek new customers in markets such as the Middle East. “Life goes on,” Lin said.

Beijing criticised Trump’s new tariffs and threatened to file a lawsuit to the World Trade Organization, but has yet to announce retaliation.

Analysts pointed to options such as export controls on rare earths — which are essential to the new energy industry — or antitrust investigations such as one recently announced against US chip company Nvidia.

Tidalwave’s Johnson said other measures could include further controls on exports of drones and electric vehicle parts to the US.

Most analysts believe Washington will impose more tariffs, particularly after the conclusion in April of an investigation Trump has ordered into the 2019 trade deal with Beijing during his first administration.

While China’s imports of US agricultural products increased slightly following that deal, its purchases of American manufactured goods decreased in 2020 and 2021 as the pandemic wreaked havoc on global supply chains.

In the meantime, some analysts believe China’s best strategy is to quietly cut its own imports of targeted US products, such as aircraft, agricultural products and medical devices.

This could hurt the constituencies of powerful Republican politicians or industry groups, such as farmers and the oil and gas sector, while waiting for a chance to negotiate a new deal.

“We don’t discount the possibility of reciprocal tariffs coming [from China], but we think they’re going to be done quietly,” said Chris Beddor, Gavekal’s deputy China research director, to avoid drawing the president’s attention away from Canada and Mexico, and possibly the EU.

“Trump is clearly still open to a deal at some point,” Beddor added, pointing to his postponement of a ban on TikTok, the Chinese-controlled short-video platform, and a call last month with Xi.

Economists said Trump’s policies could ultimately strengthen China’s economy by forcing Beijing to concentrate on difficult structural reforms, such as directing more resources towards households rather than infrastructure and industry.

China reported a record overall trade surplus of almost $1tn last year, as the country relied on external demand to offset a weak domestic economy and deep property sector slowdown.

“The irony of the first trade war,” said Song of ING, was that it reinforced China’s quest for “tech self-sufficiency”.

Others cautioned, however, that China’s economy was in a much weaker position now. In 2018, the country was able to use exchange rate depreciation, trade diversion and a reduction in exporters’ profit margins to mitigate the tariffs, said analysts at Barclays.

“The channels above have all diminished significantly, suggesting a much bigger impact on China’s trade this time around,” they said.

Data visualisation by Alan Smith and Haohsiang Ko

![Disney World prices are too expensive for Best CD rates today, [DATE]-class families](https://productiveminds.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/GettyImages-1066119168-150x150.jpg)