BBC Mundo in Venezuela

BBC News, at the White House

Nicole Kolster/BBC Mundo

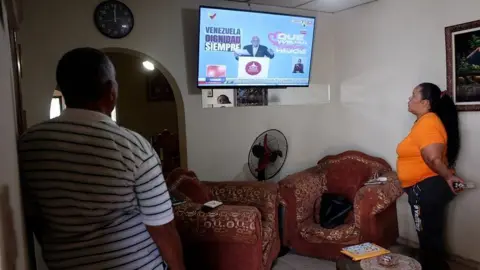

Nicole Kolster/BBC MundoIn a poor neighbourhood of the Venezuelan city of Maracay, the mother of 24-year-old Francisco José García Casique was waiting for him on Saturday.

It had been 18 months since he had migrated to the US to begin a new life but he had told her that he was now being deported back to Caracas, Venezuela’s capital, for being in the US illegally. They had spoken that morning, just before he was due to depart.

“I thought it was a good sign that he was being deported [to Caracas],” Myrelis Casique López recalled. She had missed her son deeply since he left home.

But he never arrived. And while watching a television news report on Sunday, Ms Casique was shocked to see her son, not in the US or Venezuela but 1,430 miles (2,300km) away in El Salvador.

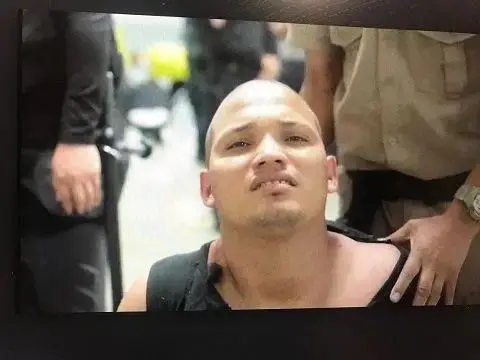

The footage showed 238 Venezuelans sent by US authorities to the Terrorism Confinement Centre, or Cecot, a notorious mega-jail. She saw men with shaved heads and shackles on their hands and feet, being forcefully escorted by heavily-armed security forces.

Ms Casique told the BBC she was certain her son was among the detainees.

“It’s him. It’s him,” she said, gesturing at a picture in which he is seated, with his head bowed, on a prison floor, a tattoo visible on his arm. “I recognise his features.”

While an official list of names is yet to be released, the family is convinced that Mr García was among the Venezuelans deported to the Salvadoran supermax prison, even as a US judge blocked the removals. They also maintain he is innocent.

The Trump administration says all of the deportees are members of the Tren de Aragua gang, which has found itself in the White House’s crosshairs. The powerful multi-national crime group, which Trump recently declared a foreign terrorist organisation, has been accused of sex trafficking, drug smuggling and murders both at home and in major US cities.

US immigration officials have said the detainees were “carefully vetted” and verified as gang members before being flown to El Salvador. They said they used evidence collected during surveillance, police encounters or testimonies from victims to vet them.

“Our job is to send the terrorists out before anyone else gets raped or murdered,” Deputy White House Chief of Staff Stephen Miller said on Wednesday.

Many of the deportees do not have US criminal records, however, an immigration official acknowledged in court documents.

Those who do have criminal records include migrants with arrests on charges ranging from murder, fentanyl trafficking and kidnapping to home invasion and operating a gang-run brothel, according to the Trump administration.

Nicole Kolster/BBC Mundo

Nicole Kolster/BBC Mundo Nicole Kolster/BBC Mundo

Nicole Kolster/BBC MundoIn Mr García’s case, his mother disputes that her son was involved in criminal activity. He left Venezuela in 2019, first to Peru, seeking new opportunities as overlapping economic, political and social crises engulfed the country, she said. He crossed illegally into the US in September 2023.

His mother has not seen him in person in six years.

“He doesn’t belong to any criminal gang, either in the US or in Venezuela… he’s not a criminal,” Ms Casique said. “What he’s been is a barber.”

“Unfortunately, he has tattoos,” she added, convinced that the roses and names of family members that adorn his body led to his detention and deportation. That is how she, and other members, recognised him from pictures released of the deportees in El Salvador.

Several other families have said they believe that deportees were mistakenly identified as Tren de Aragua gang members because of their tattoos.

“It’s him,” Ms Casique said tearfully in Maracay, referencing the image from the prison. “I wish it wasn’t him… he didn’t deserve to be transferred there.”

The mother of Mervin Yamarte, 29, also identified her son in the video.

“I threw myself on the floor, saying that God couldn’t do this to my son,” she told the BBC from her home in the Los Pescadores neighbourhood of Maracaibo, Venezuela.

Like Ms Casique, she denies her son was involved with the gang. He had left his hometown and travelled to the US through the Darién Gap, crossing illegally in 2023 with three of his friends: Edwar Herrera, 23; Andy Javier Perozo, 30; and Ringo Rincón, 39.

The BBC spoke with their families and friends, who said they had spotted the four men in the footage and they were now all being held in the El Salvador jail.

Mr Yamarte’s mother said her son had worked in a tortilla factory, sometimes working 12-hour shifts. On Sundays, he played football with his friends.

“He’s a good, noble young man. There’s a mistake,” she said.

‘We’re terrified’

President Trump invoked a centuries-old law, the 1798 Alien Enemies Act, to deport the men without due process in the US, saying they were Tren de Aragua gang members.

Despite the US government’s assurances that the deportees were carefully vetted, the move has had a chilling effect on many Venezuelans and Venezuelan-Americans in the US, who fear that Trump’s use of the law could lead to more Venezuelans being accused and swiftly deported without any charges or convictions.

“Of course we’re afraid. We’re terrified,” said Adelys Ferro, the executive-director of the Venezuelan-American Caucus, an advocacy group. “We want every single member of TdA to pay for their crimes. But we don’t know what the criteria is.”

“They [Venezeulans] are living in uncertain times,” she said. “They don’t know what decisions to make – even people with documents and have been here for years.”

Ms Ferro’s concerns were echoed by Brian de la Vega, a prominent Florida-based, Venezuela-born immigration lawyer and military veteran.

Many of his clients are in the Miami area, including Doral – a suburb sometimes given the moniker “Doralzuela” for its large Venezuelan population.

“The majority of Venezuelans in the US are trying to do the right thing. They fear going back to their home country,” Mr de la Vega told the BBC. “The main concern, for me, is how they’re identifying these members. The standard is very low.”

Many Venezuelan expatriates in the US – particularly South Florida – have been broadly supportive of Trump, who has taken a tough stance on the left-wing government of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro which many of them fled.

But in February, the Trump administration terminated Temporary Protected Status – TPS – for Venezuelans, which had shielded many from deportation. The programme officially ends on 7 April and could impact nearly 350,000 Venezuelan nationals living in the US.

“Trump’s speeches have always been strong about the Venezuelan regime, especially during the campaign,” Mr de la Vega said. “I don’t think people expected all this.”

Daniel Campo, a Venezuelan-born naturalised US citizen in Pennsylvania – and ardent Trump supporter – told the BBC that while he remains steadfast in his support of the president, he has some concerns about the deportations to El Salvador and the end of TPS.

“I certainly hope that when they are doing raids to deport Tren de Aragua, especially to the prison in El Salvador, they are being extra careful,” he said.

Among those caught by surprise by the end of TPS and the recent deportations is a 25-year-old Venezuelan man who asked to be identified only as Yilber, who arrived in the US in 2022 after a long, dangerous journey through Central America and Mexico.

He’s now in the US – but unsure about what comes next.

“I left Venezuela because of the repression, and the insecurity. My neighbourhood in Caracas had gangs,” he said. “Now I don’t know what’s going to happen here.”

Additional reporting by Bernd Debusmann Jr in Washington