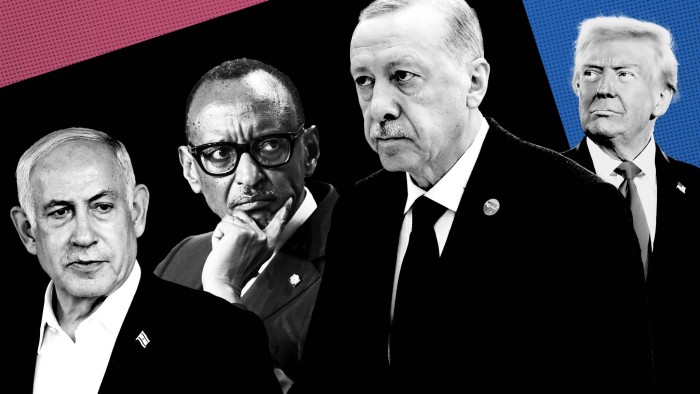

As President Donald Trump tests US democratic norms and weakens Washington’s commitment to long-standing allies, would-be autocrats the world over have taken heart.

Whether it is Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s more aggressive offensive in Gaza, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s judicial kneecapping of his main rival, or Indonesia’s president and retired army general Prabowo Subianto blurring the line between civilian and military rule, strongmen everywhere are feeling emboldened, according to many academics and foreign policy experts.

“The US crossing the line into the autocratic camp is a devastating blow for global governance,” said Nicholas Bequelin, senior fellow at Yale Law School’s Paul Tsai China Center, adding that Trump had a “clear preference” for strongman rule over democratic oversight.

“Actors think, ‘I could probably get away with what I couldn’t get away with before’,” Bequelin said. “That encourages more adventurism from countries big and small.”

Ayşe Zarakol, professor of international relations at Cambridge university, said weaker “international brakes” on bad behaviour was a factor in the arrest of Ekrem İmamoğlu, the mayor of Istanbul and the most serious challenger to Erdoğan in the more than 20 years he has ruled Turkey.

This month, İmamoğlu was brought into custody on corruption charges that he and his supporters, who have poured on to the streets in their tens of thousands, said were politically motivated.

“Erdoğan has been on this journey for a long time,” said Zarakol, who is writing a book on the history of charismatic strongmen leaders. “But with Trump in power he has concluded he doesn’t need to pretend any more,” she said. “He’s not copying Trump. He wanted to do this anyway. But he saw this as a good time.”

Previous US administrations have often condemned perceived abuses of power in other countries, but the US response to İmamoğlu’s arrest has been muted.

The state department originally described it as an internal matter for Turkey, although it later said that Marco Rubio, secretary of state, had “expressed concerns regarding recent arrests and protests”. Still, in the wake of the crackdown, Steve Witkoff, US special envoy to the Middle East, gave a glowing account of a conversation this month between Donald Trump and Erdoğan. “There’s just a lot of good, positive news coming out of Turkey right now,” he said.

Such language was giving succour to autocrats, said Mark Malloch-Brown, former deputy secretary-general of the UN. “Leaders feel they don’t need to be looking over their shoulders at the US any more, that there’s been a whole change in the moral tone,” he said, adding that Netanyahu’s crackdown on independent institutions, including sacking the head of the intelligence agency who was investigating him, echoed Trump’s narrative of “fighting the left-wing deep state”.

Many in the developing world have long accused the US of hypocrisy, supporting allies like Israel and Saudi Arabia through thick and thin and reserving what one official called its “finger wagging” for countries Washington could afford to push around.

Trump, however, has rarely been shy about his appreciation for strongmen, speaking warmly about Vladimir Putin, Russia’s autocratic leader, and quipping during his first term about China’s Xi Jinping: “He’s now president for life . . . I think it’s great. Maybe we’ll have to give that a shot some day.”

In Africa, where institutional restraints on leaders are often fragile, many politicians have praised Trump’s style of leadership, which they regard as more honest in its undisguised transactionalism. President Paul Kagame, who has dominated Rwandan politics for three decades, said last month he appreciated Trump’s “completely unconventional ways” of doing things and agreed with him “on many things”.

Kagame chose the days after Trump’s inauguration in January, when the US president was boasting about taking over Greenland and even Canada, to step up Rwanda’s stealth invasion of eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. In January and February, Rwandan-backed M23 rebels captured Goma and then Bukavu, the capitals of two important provinces in DR Congo.

“Kagame was feeling he was off the leash and could do what he liked, although he has always been someone who has questioned western double standards,” said Malloch-Brown.

One feature of transactional foreign relations, said experts, was that they were unpredictable. In Rwanda’s case, Washington has pushed back, sanctioning James Kabarebe, minister of state for regional integration, whom it accused of orchestrating Rwanda’s support for M23. Trump officials have also held exploratory talks on a minerals-for-security deal with DR Congo, Rwanda’s adversary.

Comfort Ero, president and chief executive of Crisis Group, a non-profit, cautioned against the idea that leaders were taking their cue from Washington. Kagame’s plans for eastern Congo “had been long in the making and had nothing to do with Trump”, she said.

Leaders such as India’s Narendra Modi and Turkey’s Erdoğan predated what was happening in the US, Ero said. “What is more interesting is that the US in the last 15 years has come to look more like some of these countries and not the other way around.”

Alastair Fraser, lecturer in African politics at Soas in London, agreed that Trump was as much a symptom of a global democratic drift as a driving force. In its 2024 report, Freedom House, a Washington-based non-profit, found that democracy had been eroding for 18 consecutive years, with four-fifths of the world’s population now living in countries that were either “not free” or “partly free”.

“Trump is only accelerating a trend that’s been visible for a while,” Fraser said.

The disaffection with globalisation that had helped get Trump elected for the first time in 2016 had taken root in Africa before that, Fraser said. Leaders like South Africa’s Jacob Zuma had channelled disaffection with economic marginalisation into a politics built around personality, allowing him to mount an attack on state institutions such as the prosecutor’s office and the tax authorities.

“In some senses African politics got there first,” said Fraser. “It’s possible that what we’re seeing now is an Africanisation of western politics.”

Dele Olojede, founder of the Africa in the World festival and winner of the Pulitzer Prize, said that the US still set the tone for the world. Even if, in the past, Washington often failed to live up to its own stated ideals, its championing of democracy and human rights had helped restrain bad behaviour and encouraged those fighting for civil liberties, he said.

“Those principles are now being ripped up rather carelessly by heedless people who don’t understand the majesty of that aspiration, not just for America but for all humans,” he said.

Nigeria’s President Bola Tinubu last week suspended the governor and all lawmakers for six months in oil-rich Rivers state in what Olojede said was a clear example of executive over-reach.

In the past he said, “They would have been looking over their shoulder to see what the US embassy in Abuja would say, whether there will be sanctions [or] whether people will sit next to them at dinner. Now that’s gone.”

Other autocratic-leaning leaders have openly celebrated Trump’s casual attitude towards democratic checks and balances. When a US federal judge last week unsuccessfully ordered the return of flights taking alleged Venezuelan gang members to El Salvador, Nayib Bukele, the Salvadorean leader, mocked the US courts, posting on X: “Oopsie. Too late,” accompanied by a laughing emoji.

Bukele, who was re-elected by a landslide last year, has ordered police and military forces to carry out mass arrests of alleged gang members that human rights groups say have trampled due process. A video Bukele posted last week of hundreds of shackled Venezuelans being marched into a Salvadorean prison was reposted by Rubio and Elon Musk, who thanked El Salvador’s president for his actions.

Zarakol, the Cambridge academic writing a book on strongmen, said: “What is happening in the US seems familiar to us, except that in Turkey it happened gradually over 20 years. In Trump’s second term, this siphoning of authority from other institutions is happening very fast.”

Americans, Zarakol said, might paradoxically be less alert to a drift towards authoritarianism than people in Turkey and other countries where civil society had to be constantly vigilant against abuses of power.

Bequelin at Yale said many people in the west had placed too much faith in democratic institutions and norms. “The natural gravity of the political system is towards authoritarianism, and democracy is almost an aberration,” he said.

The fight to preserve the rule of law internationally had got progressively harder, Bequelin said, as non-democratic states such as China had become more powerful. Trump’s move towards a more transactional style of foreign diplomacy accelerated a trend of dividing the world into spheres of influence where so-called great powers such as Russia and China exerted greater influence, he said.

“I’m not saying because we have Trump, China will invade Taiwan,” he said, adding that there were many other factors in Beijing’s calculations. “But is it a more favourable environment? Yes.”

Data visualisation by Alan Smith