EPA

EPA“We’ve put all our mattresses in the living room,” says Georgia Nomikou.

The Santorini resident fears the impact of ongoing earthquakes on the Greek island, popular with tourists for its picture-postcard views.

But the idyll has been disrupted this past week by thousands of earthquakes.

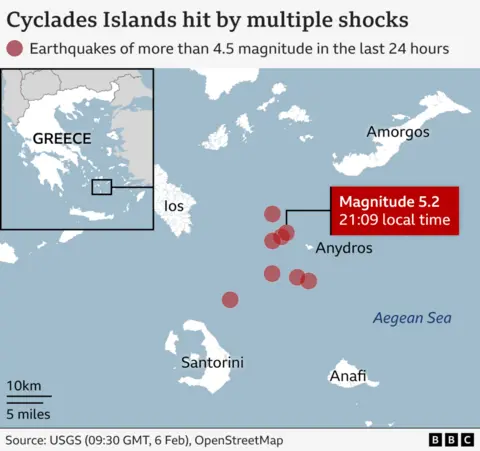

Santorini, and other Greek islands in the region, are in the middle of an “unprecedented” seismic swarm or crisis – the name for an abrupt increase in earthquakes in a particular area.

About three-quarters of the island’s 15,000 population have evacuated while authorities declared a state of emergency after a 5.2 magnitude quake, the largest yet, rocked the island on Wednesday.

Further, albeit smaller quakes, were felt again on Thursday.

The “clusters” of quakes have puzzled scientists who say such a pattern is unusual because they have not been linked to a major shock. So what’s going on?

What is happening in Santorini?

Experts agree the island is experiencing what Greece’s prime minister has called an “extremely and intricate geological phenomenon”.

“It is really unprecedented, we have never seen something like this before in [modern times] in Greece,” says Dr Athanassios Ganas, research director of the National Observatory of Athens.

Santorini lies on the Hellenic Volcanic Arc – a chain of islands created by volcanoes.

But it has not seen a major eruption in recent times, in fact not since the 1950s, so the reason for the current crisis is unclear.

Experts say they’re seeing many earthquakes within a relatively small area, which don’t fit the pattern of a mainshock-aftershock sequence, says Dr Ganas.

He said this began with the awakening of a volcano on Santorini last summer. Then in January there was a “surge” of seismic activity with smaller earthquakes being recorded.

That activity has escalated in the past week.

Thousands of earthquakes have been recorded since Sunday, with Wednesday’s the most significant yet.

“We are in the middle of a seismic crisis,” Dr Gasnas said.

Dr Margarita Segou from the British Geological Survey described the quakes as happening everyday “in pulses”.

She says this “swarm-like behaviour” means that when a more significant earthquake strikes, for example a magnitude four, the “seismicity is increased for one to two hours, and then the system relaxes again”.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHow much longer will they go on for?

In short, it is impossible to tell. There are hopes that Wednesday’s quake, which struck at night, will be the biggest one to hit the island.

But seismologists have told the BBC it is difficult to be sure. Authorities have warned the activity could go on for weeks.

Experts also do not know whether this chain of quakes are foreshocks leading up to a large earthquake or their own event.

Professor Joanna Faure Walker, an earthquake geology expert at UCL’s Institute of Disaster Risk Reduction, said some large earthquakes do experience foreshocks – elevated levels of small to moderate seismic events – before the main shock.

But what is happening now are not volcanic earthquakes, say Dr Ganas. Volcanic earthquakes have a characteristic signature of low frequency wave forms and these have not been exhibited here.

Dr Segou told the BBC she and colleagues had analysed previous earthquakes in the region with machine learning – a data analysis method able to make predictions – to learn how earthquakes in the region in 2002 and 2004 came to an end.

The magnitude of those earthquakes were not as intense as the ones felt now she said. But the “signatures” of how they started and ended could help build a picture of what patterns to look out for.

Meanwhile, additional police units and military forces have been deployed to the island to help it cope with any major earthquake.

Ms Nomikou, who is president of Santorini’s town council, said her family were staying put but had each packed a small bag, “ready to go if anything happens”.

But some islanders say they are not phased by the tremors.

“I’m not afraid at all,” says one Santorini resident, who decided to stay put on the volcanic island despite thousands of her neighbours fleeing amid the ongoing earthquakes.

Chantal Metakides insists that she would not be joining her compatriots. “For 500 years, this house has lived through earthquakes and volcanic eruptions and it’s still standing,” she told AFP news agency, adding, “there’s no reason why this should change”.