Our body fat may turn out to be a secret weapon in our everlasting fight against cancer. A new study released this week suggests that fat cells can be engineered into a treatment that literally starves out tumors.

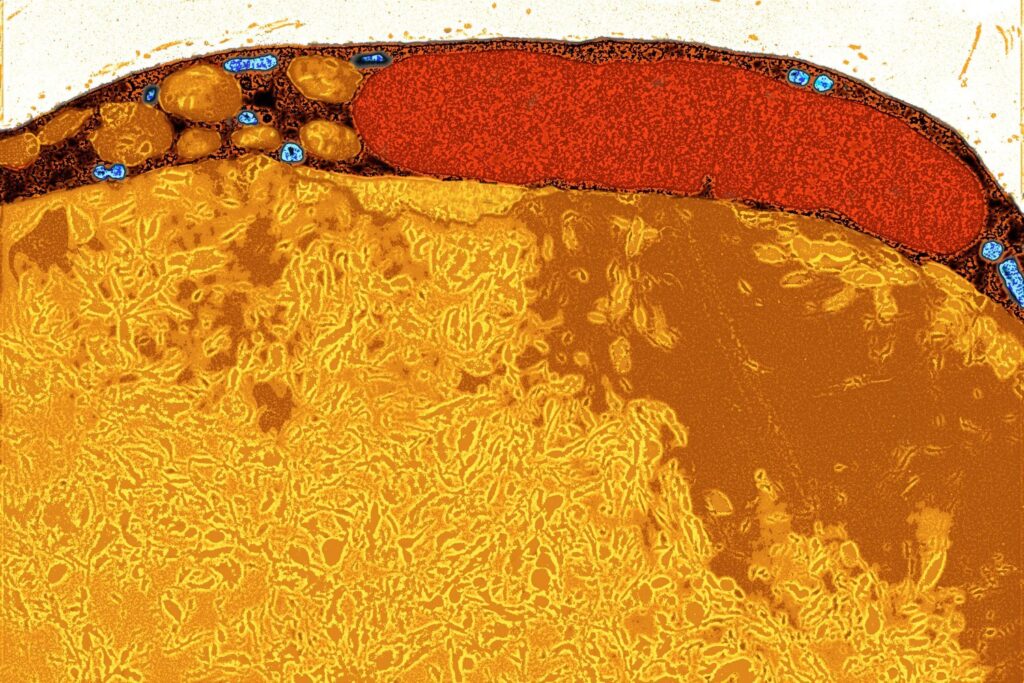

Scientists at the University of California, San Francisco, conducted the research, published Tuesday in Nature Biotechnology. Across a series of experiments, they found that repurposed and implanted beige fat cells could inhibit the growth of five different types of cancer. The findings might point to a new but relatively easy method of tackling cancer, the researchers say.

Three broad types of fat cells can be found in our bodies: white, brown, and beige. White fat cells primarily help store energy, whereas brown fat cells keep our temperature stable by burning sugar and fat when we’re cold. Beige fat cells are somewhere in the middle, capable of performing the functions of either white or brown fat cells as needed.

A 2022 study suggested that brown fat cells induced by the cold can sap away the resources needed by cancer cells to keep growing. Only a small percentage of fat cells are brown, however, and the cold therapy needed to induce this anti-tumor effect might not be safe to use in most patients with cancer (the only human case detailed in the 2022 study involved someone with relatively mild non-Hodgkin lymphoma). The UCSF researchers theorized that they could reproduce this same effect safely by turning white fat cells into beige fat cells—a transformation that scientists are now learning to perform reliably.

The researchers used a version of the gene-editing technology CRISPR to create their reprogrammed beige fat cells, keying in on a particular gene called UCP1. The cells were also sometimes modified to prefer nutrients that certain cancers are especially hungry to devour.

In various experiments using petri dishes, mice, and samples taken from real patients, the researchers found that their engineered fat cells could indeed suppress cancer growth. All in all, these fat cells appeared to counteract at least five different types of cancer cells (colon, pancreatic, prostate cancers, along with two types of breast cancer). And the cells even seemed to work when they were placed far away from the actual tumors.

“In summary, our results provide proof-of-principle results for a cancer therapeutic approach, termed [adipose manipulation transplantation], that can be further developed and personalized for specific cancers and patients,” the researchers wrote in their paper.

The team’s findings are only the start. More studies will have to replicate and expand these results before we can truly know whether fat cells are a feasible cancer treatment. But the researchers are encouraged both by the potential and practicality of their experimental therapy. Much as we might not want to admit it, we tend to carry plenty of body fat around, and doctors have long figured how to take out and sometimes relocate this fat.

“We already routinely remove fat cells with liposuction and put them back via plastic surgery,” said senior study researcher Nadav Ahituv, director of the UCSF Institute for Human Genetics, in a statement from the university. “These fat cells can be easily manipulated in the lab and safely placed back into the body, making them an attractive platform for cellular therapy, including for cancer.”

Should the team’s work continue to pay off, they envision a future where fat cells aren’t just treating cancer but can be programmed to do other tricks, such as monitoring blood glucose levels or sucking up excess iron.