Research published late last year indicated “seismic discontinuities in the Martian crust” that scientists believe could be an indicator of liquid water under the Martian surface, raising the possibility of microbial life persisting on the Red Planet.

With an ancient past not dissimilar from Earth’s, and its relative proximity to our own world, Mars has been a compelling venue for astrobiology for decades. The team’s work indicates that liquid water—necessary for life as we know it—may persist under the Martian surface, boosting the notion that microbial life could continue to eke out existence beneath the planet’s arid and rocky topsoil.

“If liquid water exists on Mars,” said Ikuo Katayama, a planetary scientist at the Hiroshima University and co-author of the study, in a Geological Society of America release, it could mean “the presence of microbial activity” in the Martian crust.

Mars rovers, landers, and orbiters are charged with understanding every aspect of the Red Planet, with all of their data shedding some degree of light on the possibility of life on Mars, even if long extinct. Over the past four years, the Perseverance rover has been soldiering along the western edge of Jezero Crater, a huge basin on the planet that harbored a lake of liquid water billions of years ago. Perseverance has picked up intriguing Martian rocks along its way, which NASA intends to bring to Earth via the Mars Sample Return program.

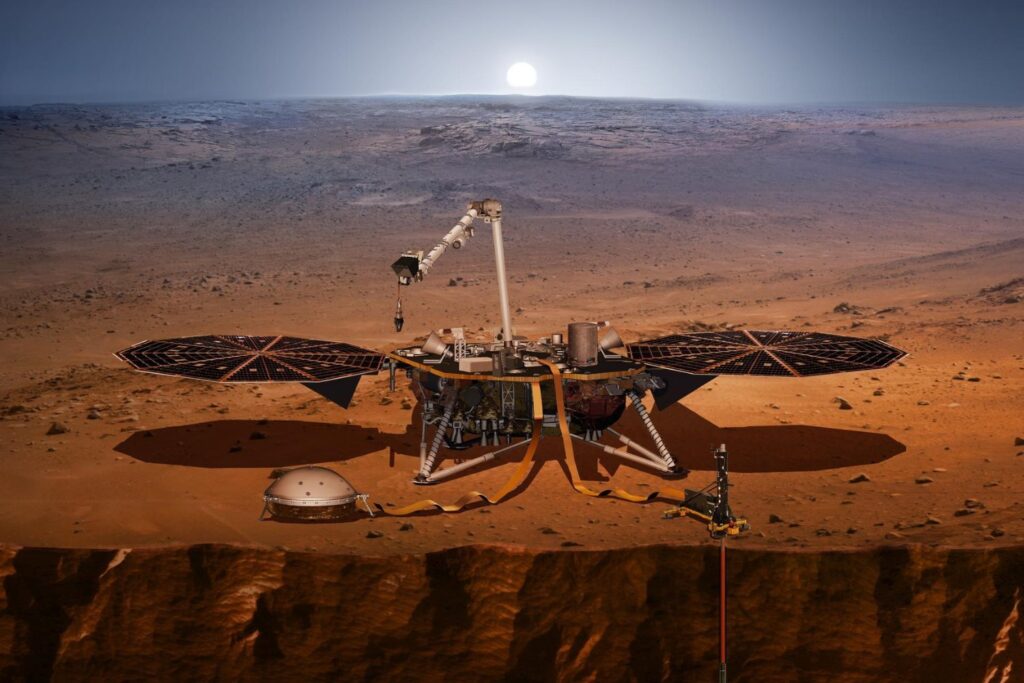

InSight landed on Mars in November 2018 and was charged with digging into the Martian topsoil, listening to winds and dust devils on the planet’s surface, and—perhaps most productively—listening to the Martian interior for signs of seismicity. Before the lander was decommissioned in December 2022, InSight detected over 1,300 marsquakes and sent nearly 7,000 images of the planet’s surface to Earth.

Some of the seismic data InSight collected indicated boundaries at 6.2 miles (10 kilometers) and 12.4 miles (20 kilometers) beneath the planet’s surface, which was previously interpreted as sudden changes in the porosity of the rock. But the authors of the paper posit that the apparent boundary may be cracks in the Martian subsurface that are filled with water.

The team measured how different types of seismic waves that occur on Mars travel through similar rock formations in Sweden. The team’s experimentation indicated that the seismic velocities through dry, wet, and frozen samples are quite different—thus, the boundaries at two Martian depths could indicate a change from dry rock in the Martian subsurface to wet rock. Ergo, the presence of liquid water on Mars.

“Many studies suggest the presence of water on ancient Mars billions of years ago,” Katayama said in the release, but “our model indicates the presence of liquid water on present-day Mars.”

InSight’s digging tool—the Martian mole—failed to dig into the Martian surface, stymieing NASA’s bold intentions to understand the planet’s internal processes.

If NASA pulls off the Mars Sample Return without a hitch, studying Perseverance’s sample cache could be immeasurably useful in determining whether life did once exist on Mars. But based on the team’s recent findings, the agency may want to consider sending an earth-mover to the Red Planet.