Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what the 2024 US election means for Washington and the world

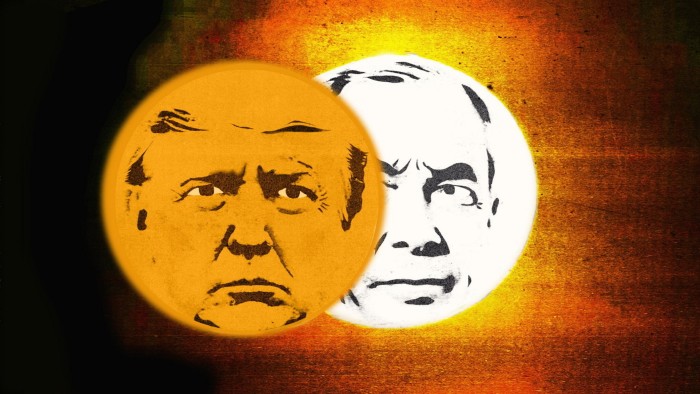

When Nigel Farage suddenly bridles at being called a populist you know something is shifting. A TV interview this week saw him not only rejecting a label he once embraced but acknowledging that his association with Donald Trump has hurt him with some voters.

His comments came amid signs that Trump is damaging parties associated with him in many countries — Canada being the immediate example. The academic Ben Ansell argues plausibly that the chaos of US politics is tarnishing the brand everywhere else, offering mainstream politics a second wind.

Ansell is not wrong to sense a shift. In the UK, Farage has faced not only the Trump backlash but also ructions in Reform UK. Superficially, his suspension of MP Rupert Lowe from the party is a clash of egos symptomatic of Farage’s long-standing intolerance of rivals. But it also reveals a strategic rift with those who seek hardline policies such as mass deportations and closer ties with the far right. Farage has long fought to decontaminate his parties, insisting on firebreaks with extremists. His declared change of mind about whether he is a populist is both about the damage being done to that brand and a recognition that Reform’s real challenge is to broaden its appeal.

Yet there are reasons for caution in calling peak populism. First, the current peak is pretty high. In countries where the electoral system facilitates new parties, they are still gaining. Even where they are not winning, they are shifting debate, forcing mainstream parties to realign with their sentiments. The so-called Blue Labour agenda now finding favour in Number 10 is just such an example: being tough on immigration, cutting foreign aid and cracking down on welfare spending.

And Trump alone cannot drag populists down unless the reasons for their success also change. This is first about economic stagnation. Until governments find a path to prosperity and people feel it in their own pockets, the challenge will remain. Underpinning that is the feeling that politics no longer works for ordinary people — that it is elitist, unresponsive to and dismissive of their concerns. As long as the mainstream parties can be painted as defenders of the status quo, mavericks will retain an appeal.

Having at least partially accepted the populist diagnosis, Labour’s challenge is to offer an alternative progressive vision of an active state that looks like a force for good. It is in this light that we must view Sir Keir Starmer’s speech on reshaping government. There is now a continuous thread that runs through Labour’s ambitions on planning, the NHS and welfare reform — a desire to remove the obstacles and processes that foster an expensive, unresponsive and underperforming system.

Starmer’s promised crackdown on independent, unaccountable regulators — what he calls the “cottage industry of checkers and blockers” frustrating the will of an elected government — is part of the same strand. From environmental regulators holding up essential infrastructure to this week’s row over Sentencing Council guidelines (appearing to propose lower jail terms for minority offenders), Starmer argues that elected leaders must stop hiding behind structures designed to shield them from blame and have the courage to take back control of decisions. Dominic Cummings and Jacob Rees-Mogg must be suppressing wry smiles.

Experience suggests not holding one’s breath for the results, not least because Labour has also been creating new bodies even as it attacks the old ones. Countless prime ministers have reached the same point of frustration with bureaucratic obstacles to change. There is also no sign that Starmer is ready to tackle the judicial over-reach or plethora of judicial reviews that stymie many initiatives, although he argues he is reducing the scope for challenges.

Labour’s vision now is a more effective state; a welfare system that encourages and assists people back into work; an efficient modern NHS, back under direct ministerial control; a planning system where major infrastructure projects are not lost to years of appeals and costs; a civil service revolutionised by digitisation; and artificial intelligence used to deliver better public services. All with more direct ministerial accountability for decisions so voters feel they can make their voices heard.

This all plays into a long-standing Starmer theme of restoring security. Building off his work to shore up international security, the prime minister will tie his ambitions to the issues that preoccupy voters, from economic security to confidence in the NHS, to crime and the country’s borders — and energy independence.

Of course, the vision is one thing. Turning it into a reality that voters notice is another. Civil and public service reform is slow, the state has a poor record with new technology. Whacking regulators only truly cuts bureaucracy if you also thin out regulation. Above all, Starmer needs an economic revival.

Rather than calling peak populism, we should perhaps say there is a mainstream moment, a chance for the parties dismissed as defenders of the status quo to offer an alternative to Trumpian chaos. Starmer has an opportunity to show he can replicate at home the grip he has shown on the world stage. Allies point to his doggedness in grinding through problems. But he will need that if he is to drive change faster and more dramatically than most predecessors. This moment may not last.