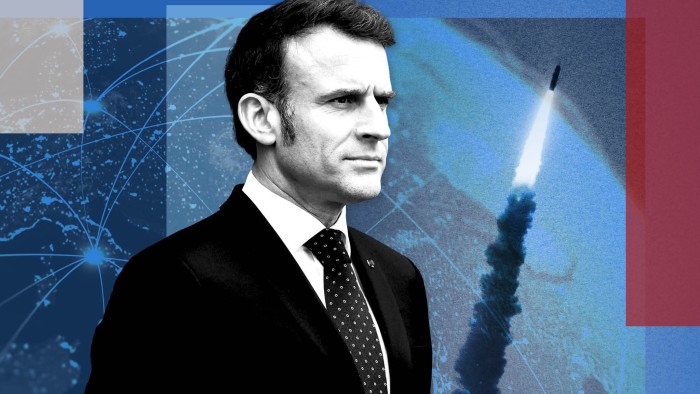

French President Emmanuel Macron has invited fellow European leaders to discuss whether — and how — his country’s nuclear arsenal could be used as a deterrent against future Russian aggression.

But his allies may not like the limitations he may choose to keep on the force de frappe.

The idea of extending the French “nuclear umbrella” to protect other European countries has taken on new urgency as Donald Trump has undermined Nato and threatened to abandon the role the US has played as Europe’s ultimate security guarantor since the second world war.

“There was never any request from a European country for such a thing since none ever wanted to question the US support,” said Hubert Védrine, a former French foreign minister who worked on his country’s nuclear doctrine.

“The debate now starting takes us into uncharted territory and it will be very hard to resolve.”

As well as the vast arsenal stored in the US, America’s nuclear umbrella includes over 100 gravity bombs stationed in Europe. These are under American control but according to a “nuclear sharing” agreement within Nato are designed to be carried and dropped by fighter jets flown by Belgium, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands and Turkey.

No one in Europe wants the US to withdraw its nuclear guarantee, but the fear is such that the leaders of two staunchly Atlanticist countries — Germany and Poland — recently said that preparations for such a scenario must begin.

Friedrich Merz, the German chancellor-in-waiting, asked for talks over whether “nuclear security from the UK and France could also apply to us”. Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk welcomed the idea, and even said Poland should consider getting the bomb itself. Lithuania and Latvia also said they were interested in the French offer.

In response, Macron offered to “open the strategic debate” with interested European countries that would last several months to determine “if there are new co-operations that may emerge”.

France has for decades said its “vital interests” — the factors that determine the use of nuclear weapons — have a “European dimension”. But Paris never defined the term, so as to keep the president’s options open and the adversary guessing, the key to all nuclear deterrence.

The Macron-led talks are expected to also involve the UK, the only other nuclear-armed power in the region. Given that the UK deterrent is already assigned to protect Europe through Nato, the onus is on Macron to show what he is willing or able to do.

Even if France wanted to somehow expand nuclear protection to Europe, experts say its arsenal of around 300 warheads — a fraction of America’s 5,000 — is too small to protect the whole region. Russia has 5,580 warheads, and has recently moved some to Belarus.

Paris also lacks tactical nuclear weapons — less powerful, shorter range weapons designed for battlefield use — and has fewer options for gradual escalation than the US and Russia. If it was under grave threat, it would carry out a nuclear “warning strike” against an adversary before destroying key targets like major cities.

Britain’s submarine-based nuclear deterrent, which uses up to 260 UK designed warheads that are delivered by US made Trident missiles, is assigned to Nato. By contrast Paris — which uses French designed and made nuclear weapons — does not take part in Nato’s Nuclear Planning Group, the forum that coordinates the alliance’s nuclear policy.

The simplest and quickest way for France to strengthen European deterrence would be for it to join Nato’s NPG to commit its nuclear weapons to collective defence, said Marion Messmer, an international security expert at Chatham House, the UK think-tank.

It would align French and British nuclear doctrine, integrate planning and facilitate training for a crisis, Messmer adds. To Russia, “it would signal France’s commitment to Europe and show that Nato, a European Nato, would remain strong even if the US disengages”.

However, this would overturn a French tradition of nuclear independence that dates back to General Charles de Gaulle who believed the US security promises could not be trusted. Macron has repeatedly stressed that a French president would always have ultimate power to decide whether to use the bomb — the same applies to Britain and the US within Nato.

Together, British and French nuclear capabilities would at least make Moscow think twice about attacking, said a senior western official.

However, “what really influences Russian decision-making is the scale of US deterrence”, he said. Europe would need at least a decade of spending at around 6-7 per cent of GDP if it wanted to emulate that and acquire another 1,000 warheads, he added.

Short of such a major expansion, France still has options, say former officials and experts. First among them would be to more clearly spell out its nuclear doctrine on how it would come to the aid of European allies, even if this one day limited the president’s freedom of action.

Camille Grand, a former senior Nato official who is now at the European Council on Foreign Relations, said France would have to become more specific. “If to every question our allies ask, the answer is just trust us, the French president will act when he sees fit, then we are not creating something very reassuring for our allies,” he said.

There is precedent for signalling expanded deterrence. In 1995, Britain and France said in the so-called Chequers declaration that they could not see a situation in which “the vital interests of either of our two countries . . . could be threatened without the vital interests of the other being also threatened”.

One possible scenario now would be a similar statement made with other allied countries, or perhaps even linked to the EU’s mutual defence clause.

Another step would be more joint exercises and training to signal to Russia that European allies were tightly bound. In 2022, an Italian refuelling aircraft took part in a French nuclear exercise for the first time, so more of this could be done. In early March, France hosted Nato ambassadors at the Istres air force base in southern France so they could learn more about France’s nuclear deterrent.

Bruno Tertrais, a leading expert on nuclear deterrence, wrote in Le Monde recently that France could send “a strong operational signal” by temporarily deploying Rafale fighter jets without nuclear warheads to the bases of “our most worried partners, such as Poland”. Paris could also seek to take part in Nato’s nuclear planning group as an observer.

Going much further would require a paradigm shift in France’s nuclear strategy and that of its European allies — one that would not be needed or justified unless the US were to truly withdraw from protecting Europe altogether.

Grand, the former Nato official, warned that it would be a mistake for Europe to seek to replicate the US nuclear umbrella, or create “a poor man’s version” of it. “We have to collectively invent something different,” he urged.